We asked Artistic Director John William Trotter to shed some light on the origins, development, and success of the HerVoice Emerging Women Composers Competition.

What inspired you to develop a competition specifically for women composers?

I think it was a confluence of several events. Over many years, I have received large quantities of unsolicited manuscripts from composers I have never met, whose work was previously unknown to me. Some of these composers could be characterized as “established”, and others as “emerging”.

Then, in 2019/20, I was elected a Visiting Bye-Fellow at Selwyn College, Cambridge. The leader of chapel music at Selwyn College is Sarah MacDonald, the first woman in 800 years appointed to chapel music leadership at either Oxford or Cambridge. There are now a total of three, I think. While at Cambridge, I happened to attend the launch of the first ever anthology of sacred choral music composed by women, an anthology edited by Sarah. That year, Sarah, who is also a composer herself, decided that every Selwyn College chapel service would include at least one piece of music written by a woman. She also published works through her own choral series at Selah Publishing in the United States. One day, she mentioned it was sometimes challenging to learn of new women composers and asked if I knew any good pieces which might be unknown to her. I did indeed, from my work at Wheaton College, where I had been involved in helping students with later stages of the choral composition process, including providing feedback to composers on their drafts and finished compositions. Over the years, I conducted several such works in performance and recording, and unsurprisingly, several of them were by women. One result of all this was that last year, Wheaton College alum Bethany Ari Randall’s O Quam Gloriosum was published by Selah Publishing.

Then, in 2019/20, I was elected a Visiting Bye-Fellow at Selwyn College, Cambridge. The leader of chapel music at Selwyn College is Sarah MacDonald, the first woman in 800 years appointed to chapel music leadership at either Oxford or Cambridge. There are now a total of three, I think. While at Cambridge, I happened to attend the launch of the first ever anthology of sacred choral music composed by women, an anthology edited by Sarah. That year, Sarah, who is also a composer herself, decided that every Selwyn College chapel service would include at least one piece of music written by a woman. She also published works through her own choral series at Selah Publishing in the United States. One day, she mentioned it was sometimes challenging to learn of new women composers and asked if I knew any good pieces which might be unknown to her. I did indeed, from my work at Wheaton College, where I had been involved in helping students with later stages of the choral composition process, including providing feedback to composers on their drafts and finished compositions. Over the years, I conducted several such works in performance and recording, and unsurprisingly, several of them were by women. One result of all this was that last year, Wheaton College alum Bethany Ari Randall’s O Quam Gloriosum was published by Selah Publishing.

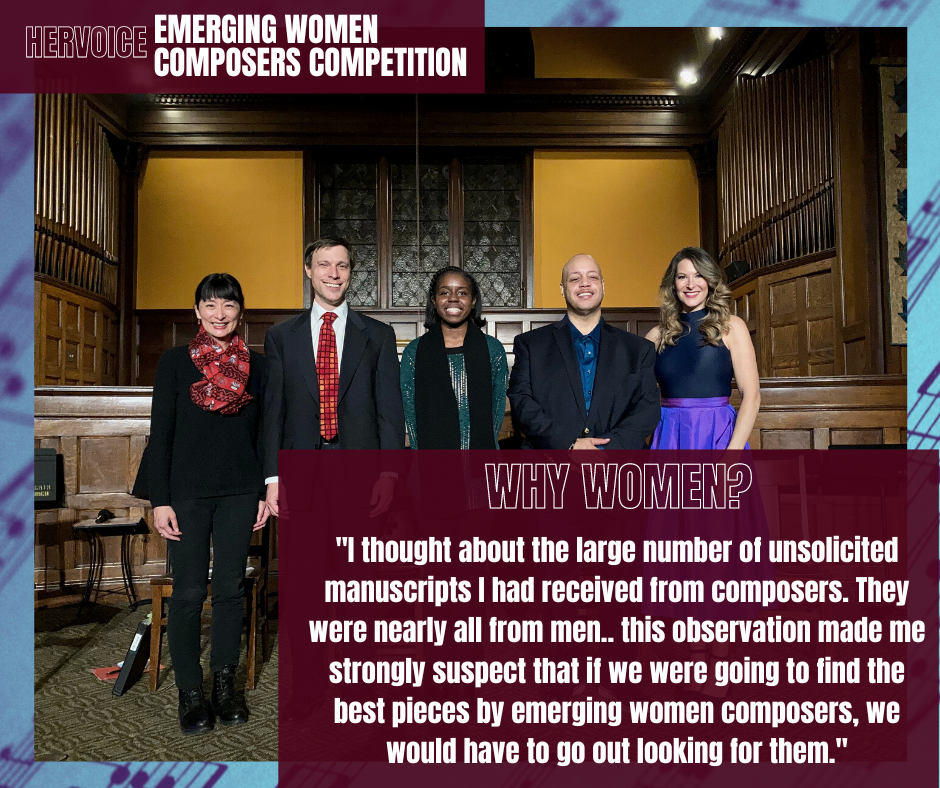

When I returned from sabbatical, I thought about the large number of unsolicited manuscripts I had received from composers over many years. They were nearly all from men. Was this because most living composers “out there” were men? If that were so, there must have been a great attrition after undergraduate study, since many composition majors I know are women. Or perhaps it was just another case, writ large, of what I had noticed with student composers: that men are more likely to “cold call” a conductor than women were. Or maybe both. Or maybe some other cause entirely.

Whatever it was, these observations were enough to make me strongly suspect that there was “gold in them thar hills” – and that if we were going to find the best pieces by emerging women composers, we would have to go out looking for them.

Why now?

COVID was very discouraging for all concert musicians, and especially singers, who found their activity labelled “high risk.” It was especially discouraging for singers just emerging into the field who saw no concerts happening, and even more so for those carrying a structural disadvantage, like women and racial minorities. Work in the arts can seem precarious at the best of times, and these were not the best of times. Ensemble members could still practice singing individually, but they couldn’t, for a time, perform together, because it was illegal. As bad as it was for singers, at least those with a pre-existing ensemble membership had one another for peer support. In a way, emerging composers were in an even more discouraging position, since much of their work is accomplished alone, and they didn’t necessarily have this peer support. Worse, emerging composers with relatively little concrete experience having their works performed, looking out at a world in the grip of a pandemic with no guarantee of such opportunities in their future, might even hesitate to self-identify as composers at all. Looking out at a world full of stages gone silent, in which so many extra-musical aspects of life seemed so deeply uncertain, who would choose to spend their time writing music for ensembles of singers?

As bad as it was for singers, at least those with a pre-existing ensemble membership had one another for peer support. In a way, emerging composers were in an even more discouraging position, since much of their work is accomplished alone, and they didn’t necessarily have this peer support. Worse, emerging composers with relatively little concrete experience having their works performed, looking out at a world in the grip of a pandemic with no guarantee of such opportunities in their future, might even hesitate to self-identify as composers at all. Looking out at a world full of stages gone silent, in which so many extra-musical aspects of life seemed so deeply uncertain, who would choose to spend their time writing music for ensembles of singers?

At the same time – and this is crucial – despite the discouragement, most emerging composers now had a resource before them the value of which they might not fully recognize, but which would likely become scarcer in the future: the precious resource of uninterrupted time. I intuited that the missing links for many such folks might be opportunity and encouragement.

I have also thought a lot about those emerging from various life stages into a world in pandemic, and how social and cultural restrictions may have a chilling effect on their ability to move on, to take the next step. Choral music isn’t everything, but it’s more than is generally acknowledged. The choral repertoire is far, far larger than the repertoire of any other musical genre, simply because choirs have been singing together for longer, and in far more regions, than any other musical art form. Why? Because choral music is an integral part of so many moments of cultural significance and has been for centuries.

In the midst of the pandemic, some folks publicly expressed doubts that choral music would survive as an art form. Those of us with the strong conviction that it would felt we had to do something to express confidence in the future, and to ensure the present darkness will not result in the loss of a cohort of choral creatives.

So, we provided a goal. We said to emerging women composers of a cappella music around the world: don’t miss this opportunity to write some music, and to share it. We want to see your work. Not only see it, but we will help you develop as a composer, and help you meet other women from around the world in a similar situation and offer advice and instruction from women master composers. And for those selected for the more intensive phase, we’ll bring your music to life, offer a significant platform and exposure, and connect you personally with a master composer and conductor working in the field today.

What role do the mentor composers and partners play in this program?

To ensure that artistic merit was core to HerVoice, I wanted to put together a panel comprised of master composers as well as of conductors, and to ensure decisions would be made “out in the open.” The deliberations of the panel are confidential, but not inscrutable. Reasons are given, and collective wisdom has a voice. I found it interesting how much agreement there was on the panel regarding which pieces most deserved to be performed, among the large quantity of worthy pieces we received.

I’ve served as a jury member for composition competitions before, and often felt as though I was comparing apples with oranges. Which is the “best” piece? Is it the piece with a compelling artistic voice, but which may contain problems – fixable problems – which flow from its unique approach? Or is it the score which is clean, clear, eminently performable, yet artistically less interesting? I think most of us would like to pick the first piece, but if the competition involves a performance, the interesting piece with fixable problems may not “come off” well in its existing form, to the disappointment of all. As a result, sometimes the jury ends up making the “safe” choice, rather than the more promising choice, which might prove to be of greater service to the field at large.

Pairing winners with a master composer to mentor them lets us have the best of both worlds. We let them continue to develop the score both before and after a live workshop with the ensemble. This gives us the confidence to choose the pieces that will be the best, even if the composer’s original artistic voice poses unique opportunities and challenges.

What do you hope this mentorship provides for participating composers?

Before leaving Cambridge, I enjoyed a memorable dinner with John Rutter and his wife JoAnne. John told me a story about David Willcocks affirming him as a composer while he was quite young, including by performing his music. The way Rutter tells this story, you can tell he’s not sure he would have had the courage to pursue composition the way he did without this early influence and support.

Unlike many other professions (elevator repair, vessel pilotage, dentistry), the field of composition does not have high barriers to entry. Anyone with a pencil and paper, or a computer, can write music. Since composition is a free-for-all, it can be difficult to figure out how best to hone one’s craft. For centuries, mentorship has been the primary route to mastery for musicians of all kinds, including composers. Palestrina would have students copy out scores by hand to learn something of the composer’s craft.

In the present day, institutes of higher learning have filled in a portion of this role. But all programs of study at such institutes, whether undergraduate or graduate, have something in common: they end. While one is a student, one possesses considerable privilege, including a community of peers, regular critique and guidance from an expert, and the opportunity to hear one’s music performed. By comparison, life after graduation can feel a bit like entering a vacuum or falling off a cliff. What is the “next step” for those who have committed to the path of music composition? Continuing mentorship will certainly play a role. But how are such relationships to be established?

So, we have set ourselves the goal, at once both modest and ambitious, of building a little bit of infrastructure to help emerging women composers, especially those who may not currently enjoy the temporary “protection” of an institute of higher learning, to continue to grow and develop.

Overall, what do you hope this program will accomplish: in the choral and composition fields, for the composers, and for Chicago a cappella?

I hope more women who are composers in fact will identify as such to the world around them. I hope women will not feel isolated or “rare” as composers just because they are women. I hope we will bring promising pieces to excellence, and excellent pieces into view. I hope all the composers involved – not just those whose works are eventually selected for performance by a HerVoice ensemble – will benefit from straight talk about what is involved in pursuing the field of choral music composition. I hope others who see our program will decide it isn’t doing exactly what they would like it to do and will start their own program to address what matters most to them. I hope our organization (singers, staff, board, volunteers, subscribers, audience members) will feel re-energized by being a part of the creative and curative process in this way HerVoice makes possible. I hope we will begin to address some of the structural inequalities in our field.

You can’t be what you can’t see. Many participants in this program have pointed out that they have never been in a “room” with women composers before. There is much lamenting in the concert music world about the fact that women seem under-represented on our concert programs. We have had approximate equality of opportunity within our institutes of higher learning for enough years to know that isn’t sufficient to address the situation. Professional and other elite ensembles are in a position to move the needle somewhat, partly because our performances tend to be heard by many people: live, in recordings, and via broadcasts.

What did you learn in the first year of the program? What surprised you? What course corrections were made for the second year, if any?

We learned that the program is already working as designed, and that the level of interest is much higher than many expected. I was humble about whether we would run the program again. After all, we are self-funding the entire thing, and you can’t go on self-funding forever. But now that we see how the program has been received, we are committing to a minimum three-year plan, with hopes to go beyond, and are seeking financial partners to enable us to fully support and develop the program in a sustainable way.