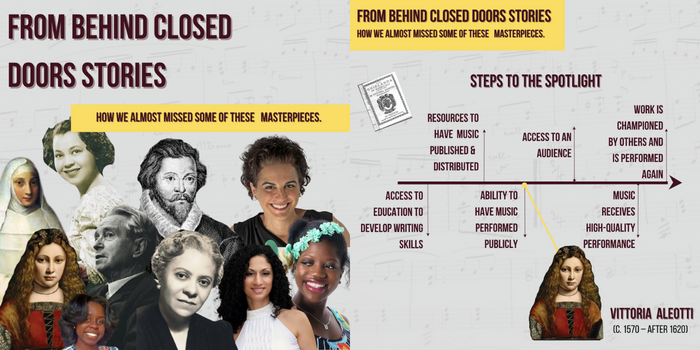

We often easily recognize masterpieces but how often do we think about the history behind how these came to be? For the next couple of weeks, we will share some stories behind the pieces featured in ‘From Behind Closed Doors‘ and the array of societal, personal, and political reasons that could have caused us to miss out on these pieces!

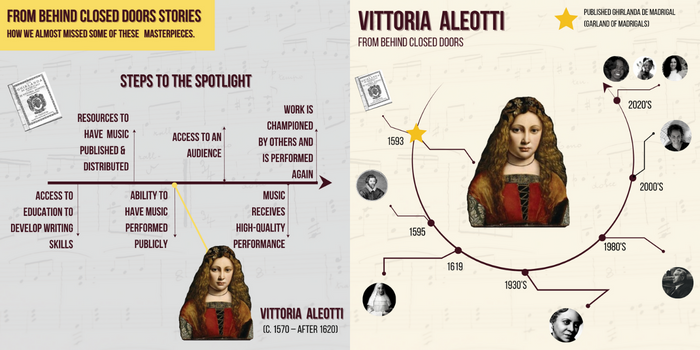

VITTORIA ALEOTTI

Our From Behind Closed Doors program will feature repertoire spanning four centuries, from the Renaissance era to the present. The Renaissance era was marked as the ‘golden age of choral music.’ During this time in 1593, Vittoria Aleotti published an entire volume of her works, collectively entitled Ghirlanda de Madrigali (garland of madrigals).

In the sixteenth century, there were several spaces for women to make music: court, the home, and the convents. These spaces were heavily affected by cultural and political implications for music-making. Often, female musicians of the time were under close scrutiny by their male contemporaries and were easily cast aside. Because the music and stories of these women were so easily discarded, there have been considerable challenges for modern scholars to uncover and understand their music.

Source: Vittoria Aleotti: Varied Performance Formats for the Madrigal and Female Music Spaces of the Renaissance by Richard Carrick

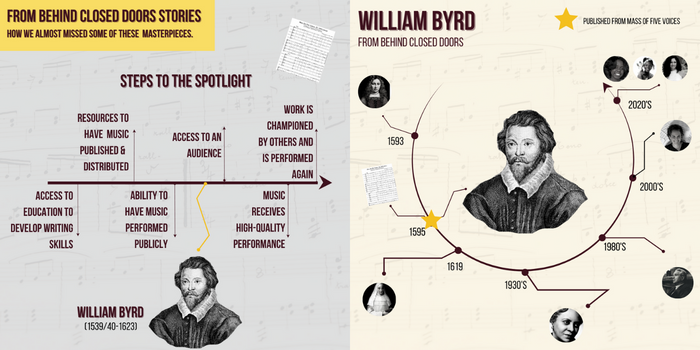

WILLIAM BYRD

Now we will dive into a composer you may know and love! William Byrd was widely recognized and esteemed as a composer during his lifetime, writing music for the (Protestant) English Court. As a Catholic, he was forced to keep his own devout faith secret as it could lead to arrest, torture, and even execution.

Being prohibited from performing his music publicly, Byrd chose not to publish the Masses as a set but individually to make them more difficult to trace, the part books are undated, with no title pages or prefatory material.

Today, Byrd’s Masses are revered as outstanding examples of renaissance polyphony, offering beautiful and inventive vocal lines, profound text settings, and compelling rhetoric.

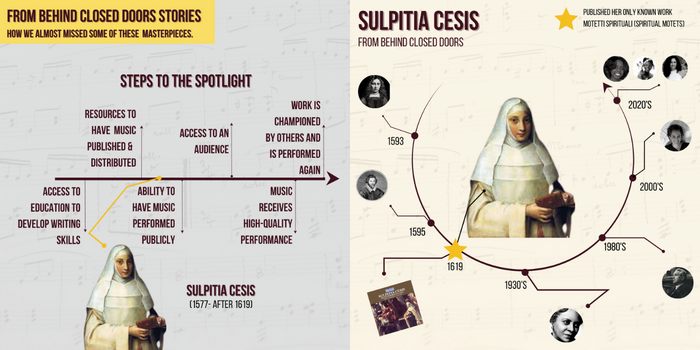

SULPITIA CESIS

PUBLISHED AT THE AGE OF 42 ![]() Sulpitia Cesis was an Italian composer as well as a well-regarded lutenist. As a nun at the convent of Saint Geminiano in Modena, Cesis found ways to circumvent strict orders from the church and included the use of cornett and trombone in her musical performances. Her only known work is a volume of Motetti Spirituali (Spiritual Motets).

Sulpitia Cesis was an Italian composer as well as a well-regarded lutenist. As a nun at the convent of Saint Geminiano in Modena, Cesis found ways to circumvent strict orders from the church and included the use of cornett and trombone in her musical performances. Her only known work is a volume of Motetti Spirituali (Spiritual Motets).

Despite the date of publication, Cesis’ motets have more in common with the late 16th-century polychoral compositions of Andrea Gabrieli than they do with the concertato style of her contemporaries. Indeed the prevalence of large ensembles over the more modern two and three-voice concerti ecclesiastic in fashion around 1620, as well as the absence of a partbook for the basso continuo (or even an organ partitura), point either to conservatism within the convent walls or to the possibility that the works were composed earlier.

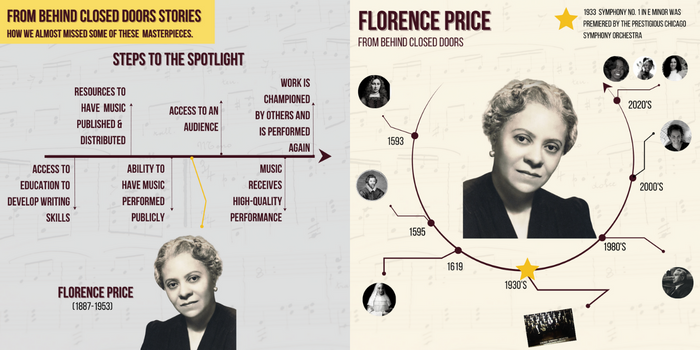

FLORENCE PRICE

Florence Price is noted as the first African-American woman to be recognized as a symphonic composer, and the first to have a composition played by a major orchestra!

Although this premiere brought instant recognition and fame to Florence Beatrice Price, success as a composer was not to be hers. She would “continue to wage an uphill battle – a battle much larger than any war that pure talent and musical skill could win. It was a battle in which the nation was embroiled – a dangerous mélange of segregation, Jim Crow laws, entrenched racism, and sexism.” (Women’s Voices for Change, March 8, 2013).

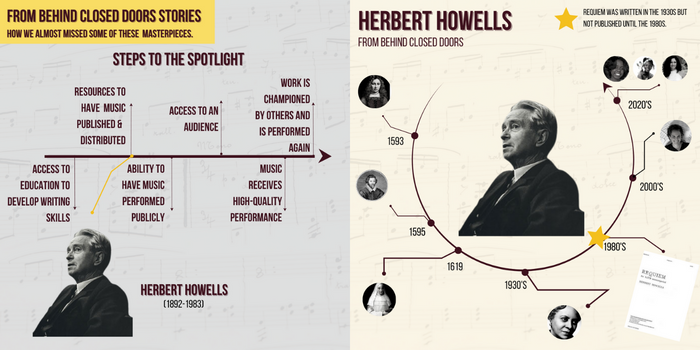

HERBERT HOWELLS

HELD BACK FOR PERSONAL REASONS. Despite his many successes as a composer, Herbert Howells did not feel free to bring all his music out into the open. He wrote the Requiem in the early 1930s, and though he utilized some of the musical material in later works, the Requiem itself was not shared for nearly fifty years and was only finally published in 1980.